The Celestial Equator: Diffractions, Reflections, Formations

A series of three videos, 2012

Diffractions: 11.39'

Reflections: 05.14'

Formations: 06.02'

Diffractions

Through scientific experimentation we investigate the world’s phenomena, perhaps as an attempt to control the physical world. Yet it can also be understood as a rite of passage, a ritual in which we travel into a different realm of possible ambiguity and transformation – into the unexpected, the unknown – and leave this realm with new experience.

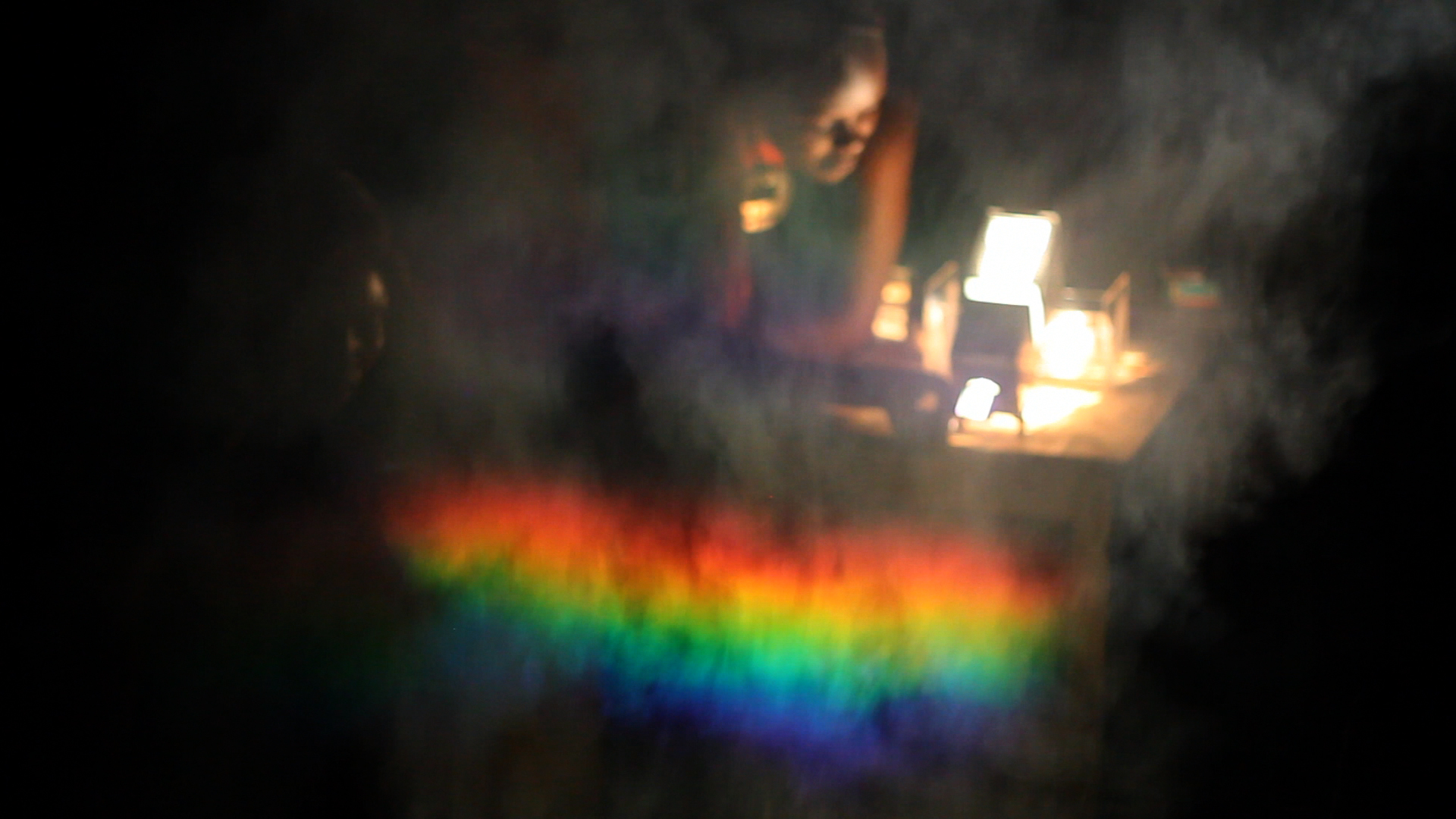

Lena Bergendahl’s film series The Celestial Equator is set in Kenya, and its two young female protagonists play the role of contemporary scientists. The first experiment unfolds in Diffractions. We encounter the women as they meticulously gather wood and prepare a fire. Their beauty, colourful dresses and slow gestures fill the screen. Later we discover it is not a domestic fire being prepared; one of the women squats by the fire and filters the light from a projector through a prism, creating an illusion of the aurora borealis, the northern light.

Lena Bergendahl’s film series The Celestial Equator is set in Kenya, and its two young female protagonists play the role of contemporary scientists. The first experiment unfolds in Diffractions. We encounter the women as they meticulously gather wood and prepare a fire. Their beauty, colourful dresses and slow gestures fill the screen. Later we discover it is not a domestic fire being prepared; one of the women squats by the fire and filters the light from a projector through a prism, creating an illusion of the aurora borealis, the northern light.

A mist of rainbow colours appears within the smoke against the now black night, and the women look at it with calm intensity. Now the women’s previous actions gain a ritualistic meaning: first preparation, then performance, and finally observation of the results.

The experiment is a modification of the Swedish poet and researcher Samuel von Triewald’s attempt in 1739 to explain the origin of the northern lights. In Diffractions, Bergendahl has removed these lights from their natural setting, the polar circle. She lets the experiment be executed near the equator, in order to investigate which differences may arise. This geographical tension is paired with the tension between the women’s material labour and the fugitive illusion into which it transforms. When the lights come to life, it is as though the physical world beautifully disappears into the night sky. The film series’ title The Celestial Equator refers to this fugitive illusion: A great circle is projected on to the celestial sphere – it exists on the same plane as the equator and is a projection of the equator into space, yet one that exists in our imagination.

The experiment is a modification of the Swedish poet and researcher Samuel von Triewald’s attempt in 1739 to explain the origin of the northern lights. In Diffractions, Bergendahl has removed these lights from their natural setting, the polar circle. She lets the experiment be executed near the equator, in order to investigate which differences may arise. This geographical tension is paired with the tension between the women’s material labour and the fugitive illusion into which it transforms. When the lights come to life, it is as though the physical world beautifully disappears into the night sky. The film series’ title The Celestial Equator refers to this fugitive illusion: A great circle is projected on to the celestial sphere – it exists on the same plane as the equator and is a projection of the equator into space, yet one that exists in our imagination.

Still images from video: Diffractions

Reflections

Bergendahl’s second film Reflections emphasizes the illusive as it abandons narrative on behalf of a play with darkness and light, an almost animated screen. In the dark night, the two women blow huge bubbles, and these fantastic bubbles become other bodies with which to interact. The lights of the night are reflected on their surfaces. The porosity of the bursting bubbles and the blackness surrounding them bring to mind the vanitas paintings of the Baroque period – sinister and silky-surfaced still lifes where decaying fruits and worm-ridden skulls represent the unknown with an air of something hidden, a worldly fragility.

Here, Bergendahl uses the bubble – which holds a scientific logic but also has a playful cultural significance – to create a poetic, mystic and aestheticized image illustrating how physical phenomena are events passing in time. She does so with a lightness, playing with the childlike joy of the bubble, leaving behind the gravity of the vanitas skull.

Still images from video: Reflections

Formations

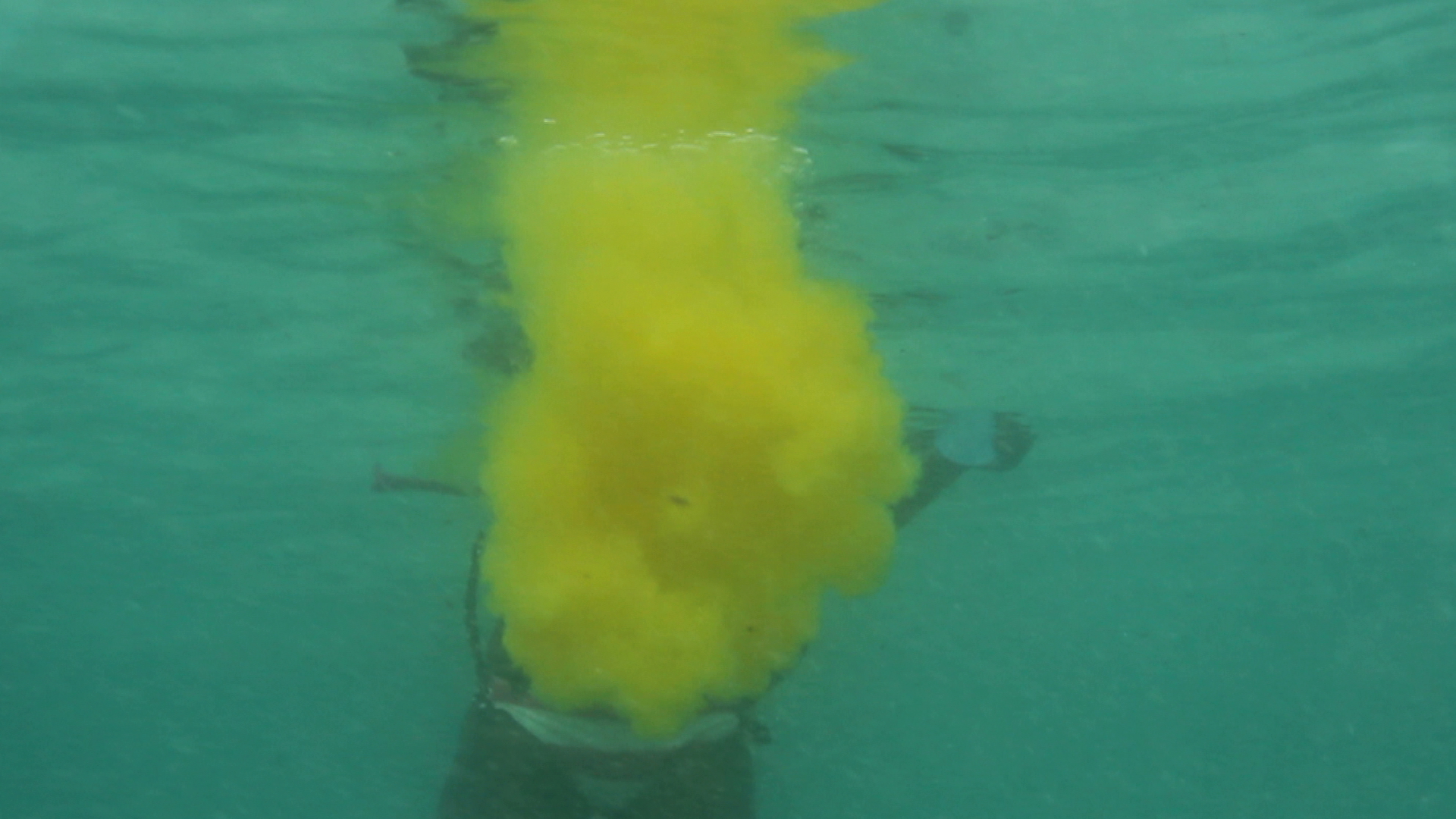

In the last film of the trilogy, Formations, the women prepare jars of coloured mixtures while sailing in a small boat on an open sea. Then, diving underwater, they pour the mixtures into the ocean and wonderful sea clouds tinted yellow, red, purple, pink, and blue cluster together, like odd sea-plants, building an architecture for the women to swim through.

The screen appears painted – it becomes an artificial landscape. This colour technique originates from 1970s sci-fi film productions, when water tanks were filled with fluid to create atmospheric effects, like the illusion of clouds.

The screen appears painted – it becomes an artificial landscape. This colour technique originates from 1970s sci-fi film productions, when water tanks were filled with fluid to create atmospheric effects, like the illusion of clouds.

Still images from video: Reflections

All three films have in common Bergendahl’s subtle play with various (pseudo) sciences, framed through a tight conceptual strategy. The ‘sciences’ come from different periods and have different purposes, a mix of high- and lowbrow. Yet the significance of each seems less important than the illusion it brings forth and the passion with which it is performed. Central is the intense visual experience of the experiment: Bergendahl lets the surface or still image vibrate, showing the passing of time through movement and pointing to the world’s ephemeral and fragile processes.

Perhaps Bergendahl´s films visualize what cultural theorist Brian Massumi speaks of when he names affect and intensity* as central to life’s constant state of flux – how the physical world never ceases to move, and we never cease to move with it. In Bergendahl´s films, we not only face the unexpected as explorers and scientists, but always live with the unexpected as a sensuous mode of being.

* Massumi, Brian: Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2002.

Text: Ida Marie Hede

* Massumi, Brian: Parables for the Virtual: Movement, Affect, Sensation, Duke University Press, Durham and London, 2002.

Text: Ida Marie Hede

Installation view: Observations of an Imaginary Dawn, Nemeshallen, Mölnlycke, 2013

Storefront Screenings, Henry Street, NYC, USA, 2013